The last letter

I got off work on Tuesday, remembering not to tell anyone where I was going, stowing my luggage under the desk, ready for a 4.30pm flit to Lancaster. My erroneously-issued and now out of date rail pass added another £170 to the thousands it has saved me.

Back in Lancaster I was clasped back into the bosom of my family, a warm and comforting place, full of wine, women and the occasional song. Long hugs from my thin daughters.

On Christmas Eve my mum rang to say that her sister had been told she's got breast cancer, and that my disabled brother had tested positive for corona. He was immediately placed under a needlessly harsh form of room arrest in his home. They wouldn't let him make or receive phone calls because they won't let him touch the phone.

As you might know, I've been writing one-sidedly to Wendy's dad for about three years, him being too infirm to reply. The letter I had with me to give to Wendy will never be read: on Boxing Day she me rang to say that he'd died on Christmas Day.

Later that day, my mum rang again to say that my brother went into an epileptic fit that wouldn't stop -- Wendy told me it's called status epilepticus -- and was hospitalised for a couple of days. He's out now and my mum has been able to ring him. He has been congratulating the "lovely porridge" served him during his stay. The staff still won't let him have the phone; a care worker holds it at two metres' distance so they both have to shout their conversation publicly.

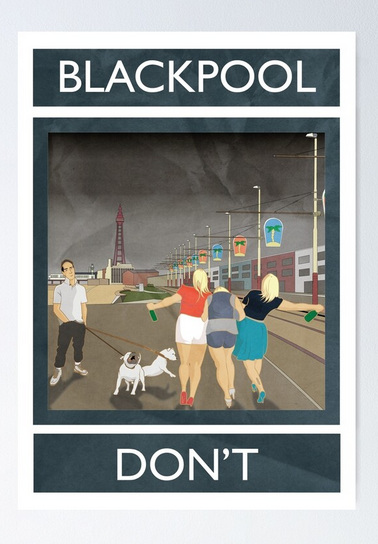

Sunday evening, at Kitty's, I am watching her face as she unwraps her present. She used to live in Blackpool, and I had bought her a poster, one in a cautionary series advising against British seaside resorts.

"Oh..."she says, doubtfully. "Oh, erm...who's the artist?" "No idea love." "Oh well. I wonder who the artist is."

I'm puzzled by her reaction, until she shows me a gloomy C19th portrait of a tired-looking man dressed in black resting his head on his hand.

On Monday I met up with Wendy for a walk with the dog. We sat on a bench with a table next to a Christmas tree decorated with merrily colourful bulbs, where we drank port and smoked dope. She gave me the best present of all -- the last book that her dad had read whilst he was still able to read, Sweet Thursday by Steinbeck, with a dedication from the two of them to me.

She read me the obituary that her brother has prepared for the local papers, about his roistering life, financially supported by his career in a smokier and more alcoholic journalism than we have today; and the first paragraph of Cannery Row[1], which she'll read at his funeral on Thursday. "These were his people," she said.

We then went round to Kitty's, who, in a typically simple, kind act, had made us all soup. I wasn't sure about to what degree of talking about her dad, or wanting us to be merry, that Wendy wanted, but it was more important that we were just there, chatting, Wendy holding it back but still taking part.

Kitty made a comment about Wendy looking "beautiful", which means completely different things for a man and a woman. I jumped in to wrest the word from the sexless sisterhood's interpretation, and reminded her that she is stunningly beautiful, in the proper sense of that verb.

I came back via Leeds, where I spent a freezing cold twenty minutes in a churchyard with my old uni pal. I was hoping he'd allow me into their house, but we stood on the heatsink flags instead. I had an expensive coffee I didn't want.

At Leeds station, I made the decision to have a shave. I have never felt glad to wear a face mask until then, since the cheap plastic razor left me with several cuts, and the inside of the mask is now all bloody.

Walking home, I suddenly realised that I'd left my holdall on the train. Everything else can be replaced, but not Bill's book. I'm very much hoping it finds its way back to the lost property office in Bristol. I've done this before -- readers with long memories will remember the time I joined my family to travel to Brittany on our hols, and arrived with only the clothes I was wearing. The rest were last seen on a luggage rack on a train, and were never returned.

[1]

Cannery Row in Monterey in California is a poem, a stink,

a grating noise, a quality of light, a tone, a habit, a nostalgia,

a dream. Cannery Row is the gathered and scattered, tin

and iron and rust and splintered wood, chipped pavement

and weedy lots and junk-heaps, sardine canneries of corru-

gated iron, honky-tonks, restaurants and whore-houses, and

little crowded groceries, and laboratories and flop-houses. Its

inhabitants are, as the man once said, "whores, pimps,

gamblers, and sons of bitches," by which he meant Every-

body. Had the man looked through another peep-hole he

might have said : "Saints and angels and martyrs and holy

men," and he would have meant the same thing.

I have a substantial meal

Me and Mel meet up on the bus. We are stealing a few miles across the boundary into Bath and Northeast Somerset, where one can go to a pub, as long as one eats a "substantial meal".

The bus gets to Keynsham, (it's pronounced "cane-shum") where we have forty-five minutes to kill on a very cold evening.

In Sainsbury's, for want of anywhere warm, we walk ridiculously round the aisles, fingering objects we don't want until we get to the alcohol. I get a bottle of cider and she gets one of those mini bottles of wine. I am urgent for a piss so I go off to this tiered (sorry) garden area behind the now closed Sainsbury's cafe.

I get back and Mel has acquired company, with a teenage boy sat cosily next to her on the short bench. He's with a gang of yoof, who are admirably ignoring the harsh conditions by standing around eating takeaway food.

Me, Mel and him, pelvises in touch, are chatting away. He wants to return to his own though. I hear him say "yeah but you got to be fly or you don't get anywhere."

Suddenly two staff from Sainsbury's come out, looking busty and officious. The yoof scarper and we are suddenly alone.

After we'd finished our meals, we ask the waitress for another glass of wine each. We are not allowed, because we have stopped eating, which made me wish we'd left a morsel on the plate. It's a let-down of an evening, and my chivalrous gesture to pay -- for one course each and a bottle of wine -- set me back £60.

On Saturday Hayley came over. I met her at the bus stop, where she was in need. We went down the side of the Turkish supermaket where she pissed in the alley while I held my coat open like a gallant flasher.

We sat in the park drinking cider. An eighty-year-old man came up to us and started forcing out some fractured bits of Nessun Dorma. After a long ninety minutes of Hayley's complaints on a loop about her impotent boyfriend, the sparkling side of her came out. "The trouble with gay men is that they listen to you."

We had "arranged", in a Haylean sense, to meet up tonight for a dance and a drink at hers, but as you can see, dear reader, I'm writing this rather than sucking on a crack pipe with a sexy miniskirted younger woman.

I left Hayley kissingly, and made hurried preparations for another night across county lines: to Bath, where we were staying overnight with her friends.

The evening was dull work for me, listening to them talking about their years on a Greek island where they all used to live, and loud, prolix anecdotes from Neil, who hasn't heard of turn-taking. It dismayed me when the girls started talking together and I was cast as Neil's sounding board. On top of this, jarring pop-rock given a form of attention I find impossible to understand.

To attempt some noise abatement, I chewed and screwed up some paper and stuffed it into my ears. I excused myself to bed; Mel came up later and wanted sex, sighing as she gave up fiddling with a useless cock.

The morning was entirely different though, and it was only by stopping another wave of mutual arousal that we got downstairs before midday.

There was time for one last intimacy though. "Mel, I've got some paper stuck in my ear. I rolled it up last night because it was getting really noisy. Can you get it out with your fingernail?" Taking advantage of the well-prepared way in which women travel, I plucked it out with her tweezers.

Isla and Neil know a first-rate pub where a small bowl of chips counts as a substantial meal, your licence to drink to your heart's content. We were legislatively hungry though, and ordered pie and chips.

We got talking to the bloke at the next table; in the toilets, I got chatting to someone who was standing in the cubicle swigging from a bottle of whisky, which he started sharing with me. It was exhilerating to have the unpredictable company of strangers again.

Isla and Neil went home; me and Mel stayed for another pint, and more stroking, my fingers in her hair, the selfish shunning of others in a house made for society.

Three long texts to Mel at half past one this morning, full of sex. Sexy Ex-Boss has invited us round on Saturday to The Big House, Me and Mel are staying overnight. Mel's going to wear what I've bought for her. She doesn't seem to mind me using her like this. The lack of negotiation is a turn-on.

I accidentally buy 154 stamps

I am so robbed of time with this job. I am neglecting everyone.

I miss my old life. I went to Hayley's after work the other day. The front door was wide open, music playing. Hayley, just the same -- selfish, physically desirable, funny, talking over me, loveable. "I feel like an ant in a box," she said, about her gradual estrangement from her boyfriend. Which I found first mysterious, then hilarious. She was slightly stooped over the crack she was preparing for us, an oval ladder in her tights just below her skirt hem. I went to hug her for saying it, keeping a secret smile from forming.

She's working in security on a film set, getting thirteen pounds an hour -- three pounds more than I get. I was tired, so was she. As I left we kissed lips to lips. With my cock stiffening, I opened my mouth to try to encourage her to open hers, but she refused such an intimacy.

Back here, Cath is irritated that I have spent the weekend with Mel rather than cleaning. It's my turn to do it and she likes it to be done at the weekend. On Sunday I am happily tired from wrapping myself round Mel at her friends' house, so I start on it when I get in from work on Monday. She makes a fourteen-year-old's show of stomping upstairs as I hoover the hallway.

Later, she's downstairs again and I apologise to her if I chucked her out of the living room. "Why do you start it at half past six on a Monday?" she cries, with a passion fueled by the lack of regulated discipline in my cleaning behaviour. "Cath, I've got a full-time job and a girlfriend now." "But you had all Saturday to do it!" betraying how little interest she had in the gripping Second Round FA Cup tie in which Morecambe beat Solihull Moors in extra time to win a third round place away to Chelsea. "Well, it's too bad," I said, and she went back upstairs, my admonishment complete.

I was rattled by all this and wanted to go out, feeling the miasma of Cath's disapproval as I felt my way down the stairs in a house thrown into darkness at nine o'clock. Anxious people are never content only with fucking themselves up but see those closest to them as unsigned recruits. I texted the woman I met a few weeks ago outside the pub. "You about? Bored shitless. Just had an argument with my landlady. I'm going down the park if you want to come. I can get us some drink." She didn't reply but I went down anyway.

It was a mild still night, the plane trees almost denuded, just thin witches' fingers left; but most of the magic shouted down by the cars. The council has taken a third of a small park and given it over to foam-floored play spaces for children, giving us alkies fewer seats to share. There were four men there I didn't know. We didn't approach each other. I smelt an effort on their speech, something a bit dissembling.

The same evening I accidentally bought one hundred and fifty-four second class stamps. My mother sent me five hundred pounds the other day. It comes from the meagre savings of a woman who has never owned property, and has nothing but the state pension to live on. She refuses to accept any refund, so the ruse was to buy her fifty pounds' worth of stamps, as she's a keen letter writer.

I could have sworn I got a message saying the transaction hadn't gone through, so I tried it again. Same error message. Then I got two emails from paypal thanking me for my business, with two orders of fifty-two pounds to Royal Mail.

Push it further

Two fireworks have gone off recently in the goldfish bowl of us, which I'm tardy in mentioning. I'm occupied with Mel, and I blame the job, which leaves little time for reading and writing, let alone long afternoons in the park with my confrère of alcoholics. Having a job has a sour flavour, not just discipline and punish, but discipline and punish and reward, in a cheap currency that capitalism has worked to make necessary for all but the most determined. The latter are the best people, and I'm involuntarily being drawn away from them.

A month ago, Crinklybee, my right-column man, invited me to a book launch in the contemporary setting, for a volume which included one of his blog's best posts turned into very short story form. The evening was a transatlantic affair, hosted with good humour and brevity from New York by one of Crinklybee's in-laws.

I remembered the original post well. It's about him breaking something valuable and all the tenseness that comes from not having the language and social knowledge to cover the shame, which only creates a guilty pleasure for the reader.

In its spoken form, though it was something else. It had his accent, and shorter sentences. In the written form, Crinklybee is a master builder of long sentences, which make you feel like you're being taken by the hand through a series of rooms each full of curios. Jenga-like, you daren't risk taking one clause out for fear of jeopardising the whole floor.

Whilst I am completely unaffected by any aching, longing desire to get published, I was delighted to see Crinklybee so deservedly elevated. The book's available from the devil for less than what a man who moves to Bristol might pay for his first pint in that expensive city. No need to buy it as a favour; buy it because of the quality of the writing.

Some people leave blogging for a while, and some have five years between posts. Miss Underscore suddenly emerged from beneath a pile of perfumed confectionary, to relaunch Parma Violet Tea. My one and only communication with Miss Underscore was almost exactly five years ago, when I told her by email that "I find your blog very moving and would love to tell your readers that too."

The first of her new stories is Lost, Part 1. I'm a bit behind with both Crinklybee and Miss Underscore's sudden loquacity, so I'm surreptitiously printing them both off at work to read in a relaxed setting. What are offices for, really?

Sexy Ex-Boss offered a bedroom in the Big House to us on Saturday. Mel wore her dog-toothed black and white dress and black tights. We all got on and I managed to keep the coke down to one line. They turned the ever-pestering television off and we were elevated into Alexa choosing the music for us. I wished we could have just enjoy the sounds of us talking, and the dogs' snoring, but it flowed well, two women released into talking about offspring and cancer and bereavement and money in a way that they wouldn't with me alone, with interludes of me talking about myself and Neil offering things designed to take me into a male envelope, whilst I found the female chat more interesting.

She never gave the slightest flicker of acknowledgement of our flirting, which made her higher in my eyes.

"In my book I'm calling you Sexy Ex Boss.

--Who's that?

Oh, I don't know, some bird I met in D--- Likes her gin.

--Oh must be a classy bird then?

Very classy. Well dressed too.

[A minute passes]

Listen, [real name] I'm going to have to go before this gets out of hand. Night night x

--Lol! Sexy Ex-Boss. Less of the Ex!

I can tell you Sexy Ex Boss, the first bit's still true Xx"

What a cunt, when I'm going out with Mel.

I bought Mel a couple of things. "I want to turn you into a tart for my pleasure Mel." She's not used to walking in them but she's going to get used to walking in them. As she was trying them on she had one leg crooked up on the bed and the other on the floor. I wanted to freeze her there. Her white knickers, her unmeant pose.

We're still working the sex out a bit. She said "I'm a very selfish lover", and she does get lots of attention, so it was a move forward, literally, to straddle her at shoulder height and push my cock into her mouth for the first time. She has offered several times in the past, but I like neither asking nor granting permission.

In the morning we ordered breakfast in, something I've never done before.

"What do you reckon the delivery man's called?". "Abdul", she said. "No look, it's Elvis, and it says he's on a bike." She played that Kirsty McColl track about the deluded bloke in the chip shop. When he arrived though, Elvis had gone sick, and Abdul had taken on the job. It all felt luxurious, beyond my income and class.

Underwear

In a training room at the hospital, I am sitting through a long afternoon of assessing the load and keeping your back straight, the fire triangle, and how you've got to be nice to gay people.

In front of me, a cleaning supervisor who has been sent on a refresher course sneezes, for the third time, into his hand. As he withdraws it from his face, a string of mucus hammocks between his mouth and his hand. He puts his hand onto his thighs, redoubles his interest in the slide, and wipes the slime on his trousers.

Me and Mel go to Wells on a day out. The jolliest seats on the bus, at the front, on the top. In the cathedral, we see the second oldest working clock in the world, which every quarter of an hour has a jousting scene popping out like a cuckoo clock, in which the same wooden jouster has been knocked off his horse since at least 1340.

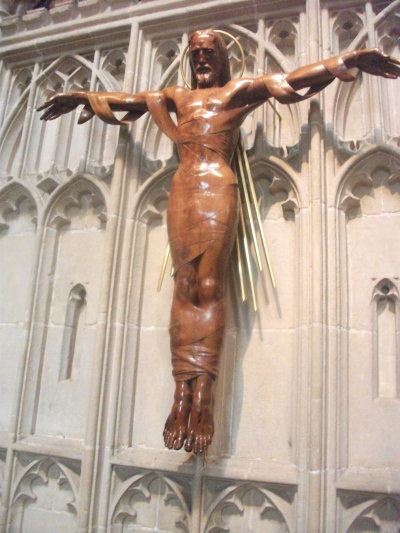

That was impressive, but the thing I remember most was Jesus in a 60s sculpture, styling his yew corset.

Near the bus station, we find a micropub run by a misandrist South African woman in her sixties who keeps telling me that I won't like various of her ciders, as "men don't like that." We sit on an old sofa in what was recently a living room, and I deliberately have the one she is warning me off. I tell her, truthfully, that it is delicious. I feel my head melting a bit. I fall asleep against Mel on the bus, before waking up and guiding her hand on to my hard cock.

We spend a rather intense night at her friend's house. The drink and dope is plentiful, as is the resentment. There's an eight-year age gap between her and her seventysomething husband, and the drunker she becomes, the more complaining and flirty she gets.

Over and over again, she says she wants a toy boy and not "this old man", who is sitting next to her. He takes this with resignation, coping with cruelty. I tell her that she's being horrible, "and it's no good looking at me Trish, 'cos I'm taken now." Mel repeatedly rescues the situation by getting us all up and dancing.

We go to bed and Mel kisses me forcibly, almost violently, pinning me down, which turns me on. I tell her I'm buying some things for her to wear, or to take off rather. (And browsing hosiery websites is enjoyable in itself). She sounds hesitant. "I don't know...I think I might feel ridiculous." Patience, looby.

In the Suffolk Arms on the last day before we're forced into house arrest again, it's crowded, and everyone's stoned and chatting. As the crowd thins out a bit, Mel delights me by standing up and dancing, and I join her immediately. It's probably illegal now. "Oh God, here go the lovebirds again," someone says, and the best track from a rock-based, white man's pub jukebox comes on -- Grandmaster Flash's The Message -- and I'm showing off in suburbia to my girlfriend, knowing most of the lyrics.

The new job started on Monday. I'm not sure. Everyone congratulates me; I can't see what for. Les Murray, reading at Lancaster Literature Festival decades ago, had a line "Any job's a comedown from where I'm from." I've lost a great deal. It's a divorce from the smackheads and alkies down the park, and Hayley, and whole days spent drinking. When I talk to others about its advantages I speak in a voice that isn't my own, in something of the same way as I do when I tell Mel that I love her, my one false note.

We have a family conference over the phone, in which we resolved that we are going to spend Christmas together, along with Fiona's very likeable ex, regardless of any new rules of association.